A practical guide to modern teaching evaluation

Dozens of institutions are piloting new ways to evaluate college teaching beyond student surveys. Here are the six steps they’re taking to fix a broken system.

A new consensus is beginning to emerge on how to evaluate college teaching. Research has consistently shown that traditional methods, which rely heavily on student evaluations of teaching, do not accurately measure teaching effectiveness. An AAUP survey of 9,314 faculty found that less than half believed in the validity of student evaluations, and an influential 2020 paper found that even validated survey instruments can lead to unfair outcomes. And yet, the lack of a widely accepted alternative has left many higher ed institutions assessing instruction in ways that are both deeply unpopular and methodologically unsound.

I recently interviewed over 20 institutions about their efforts to modernize how teaching is evaluated.1 Across institutions of different types and sizes, everyone seemed to agree that the current system is broken—very broken. One administrator told me that students at their institution used to throw drinking parties to fill out their mandatory course evaluations. At a different institution, a professor shared that his colleagues are known to crack open a bottle of wine before reading their student comments. There has to be a better way to evaluate college teaching; we can’t just keep numbing the pain.

The good news is that the repertoire of available methods for evaluating teaching effectiveness is finally starting to expand. Over the past decade, tremendous strides have been made to modernize how colleges assess instruction in any modality. Early progress was forged by:

Over $5 million in research funding through two landmark NSF grants: DeLTA at the University of Georgia and TEval at Colorado–Boulder, University of Kansas, and UMass Amherst.

Influential support for reform from higher ed organizations such as AAUP, AAU, and the National Academies, as well as disciplinary associations like the American Sociological Society.

Reforms at vanguard institutions, such as the Holistic Evaluation of Teaching initiative at UCLA and the Teaching Evaluation Task Force at the University of Oregon.

The 2025 publication of Transforming College Teaching Evaluation marked a turning point in the sector-wide movement for change. The TEval approach is now widely recognized as the “gold standard” in teaching evaluation, and dozens of institutions have adapted their methods over the past five years.

“The research on how to evaluate teaching quality is well-established, but it isn’t being put into practice.”

The question facing most institutions today is not what should replace traditional evaluation systems but rather how to implement modern approaches within a particular context. As one change leader expressed, “The research on how to evaluate teaching quality is well-established, but it isn’t being put into practice. We saw our task not as coming up with a new system of evaluation but as change managers to understand why people weren’t adopting best practice.”

Six Stages of Change

Despite significant differences, my conversations with teaching evaluation leaders evinced a strikingly familiar pattern of change across a range of institutional settings. In particular, I found that teaching evaluation reform generally follows this six-stage pattern:

Someone within the institution recognizes a problem with traditional teaching evaluations and commits to doing something about it.

An objective and strategy for change is determined, and an official channel for making change is established at the department, school, or university level.

A research-informed framework that defines effective teaching across multiple dimensions is adopted.

Structures, guidelines, and policies for evaluating multiple sources of evidence are formalized.

The new evaluation process is evaluated using real data and revised over time.

The new evaluation process adopts modern technologies and reaches a sustainable steady state.

In this post, I go step-by-step through each of these stages, outlining the key actions to take and how to avoid potential roadblocks that might arise. Making meaningful changes to the way teaching is evaluated does not have to be a long, arduous, or arcane process forged in isolation. By learning from reform efforts that have worked for others, institutions can confidently chart their own next steps toward change.

Of course, there is not one “right” path to progress. The aim of this guide is not to tell you which path I think you should take, but to outline a variety of overlapping pathways that have found success at institutions around the country. I endeavor to provide a diverse toolkit that can help you select the right tools for your context.

Before digging into the six stages, let me first clarify what “modern” teaching evaluation is and which institutions have already started to implement change. At the end of the post, I also provide a bibliography of the scholarly research that serves as an emerging evidence base for this work.

What is “modern” teaching evaluation?

“Modern” approaches to teaching evaluation have essentially two key features:

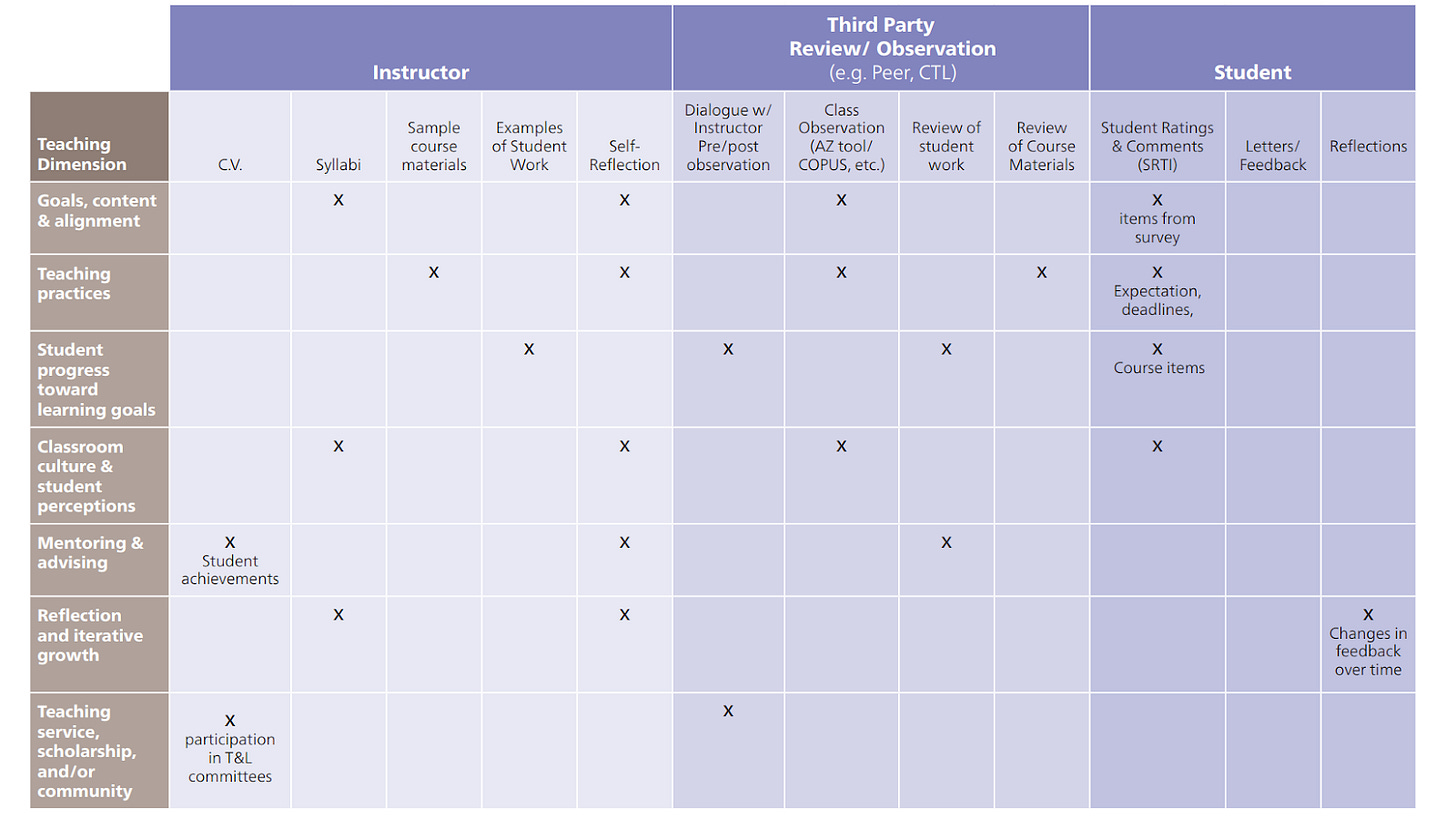

Multiple dimensions of effectiveness. A key feature of any valid assessment instrument is that it clearly defines the construct to be measured. Student course evaluations tend to ask students to rate an instructor’s overall “quality” and are often boiled down to just one number. To clarify what an institution means by “good” teaching, modern approaches to evaluation use a framework to specify multiple “dimensions” or “elements” of effective teaching that align with research-informed practices. These frameworks are often called “teaching quality frameworks” or “teaching effectiveness frameworks” and usually have between four and seven distinct dimensions, sometimes with subdimensions or practices within each. TEval’s framework, for example, has seven dimensions: goals, content, and alignment; teaching practices; class climate; achievement of learning outcomes; reflection and iterative growth; mentoring and advising; and involvement in teaching service, scholarship, or community.

Multiple sources of evidence. Modern approaches rarely discontinue the use of student course evaluations altogether. Instead, they insist that teaching is too complex to be evaluated by any one metric. The aim is therefore to encourage data triangulation by compiling a portfolio of evidence that can speak to a wide range of instructional competencies. Instructors are often asked to provide evidence to support each dimension of effective teaching within a given framework (as opposed to evidence of overall “effectiveness” or “quality”). They are also encouraged or required to provide evidence from multiple “lenses” or “voices,” of which there are three: the instructor or self lens (such as a CV or teaching statement), the student lens (such as course evaluations or samples of student work), and the peer or third-party lens (such as a classroom observation or a peer review of course materials).

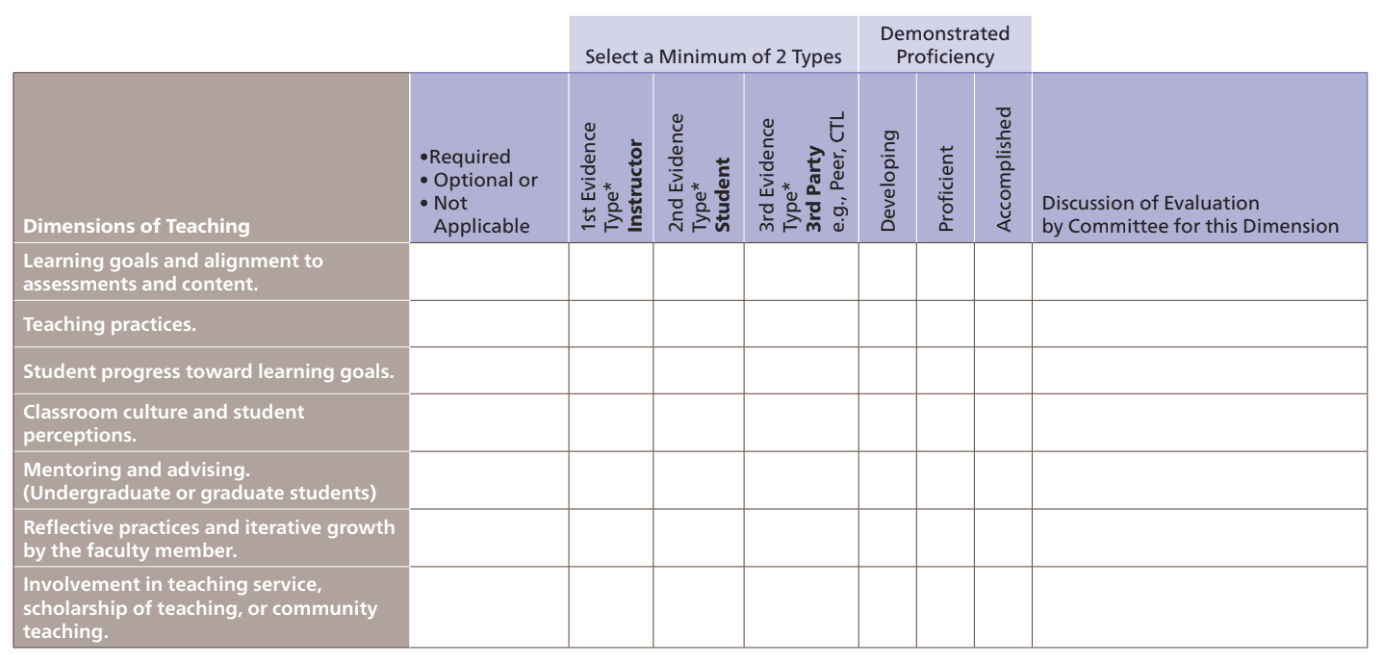

Modern approaches generally culminate in a matrix like the one below, allowing instructors to include multiple sources of evidence to document their proficiency across multiple dimensions of effective teaching.

By contrast, “traditional” approaches rely primarily or exclusively on student course evaluations. While traditional approaches may also require faculty to submit other documents, such as a teaching statement, it is the student survey results that ultimately matter in practice. Traditional approaches evaluate teaching “quality” in the abstract, deferring to the subjective definitions of student survey respondents and evaluation reviewers. Even certain implementations of teaching portfolios can thus be considered traditional if there is no rubric by which the documents within the portfolio are evaluated and weighted (which generally results in once again falling back on student survey scores in practice).

“I know literally nothing about my own promotion process, except for the fact that I was promoted.”

A further difference is that, in most cases, traditional approaches to teaching evaluation are primarily summative and do not emphasize actionable feedback to instructors under review, if they provide feedback at all. As one faculty member told me, “Evaluation felt like something that was done to me. I know literally nothing about my own promotion process, except for the fact that I was promoted.” Another told me, “Almost nobody thinks our evaluation process makes you a better teacher.”

Modern approaches seek to align evaluation with development. While they are still used summatively to make decisions regarding tenure and promotion, modern evaluation systems also provide formative feedback to guide instructional improvement over time.

Where are teaching evaluation reforms already underway?

Many institutions have already started to transform the way teaching is evaluated on their campus. These models can help build confidence that change is possible as well as provide concrete resources about the multiple paths change can take.

Institutions that have adopted reforms include:

Bates College

Dalhousie University (Canada)

Northwestern University

Stage 1: See the Problem as Solvable

Key Steps

An individual or group becomes deeply dissatisfied with traditional approaches to teaching evaluation and commits to doing something to fix it.

Potential reformers learn about modern teaching evaluation systems used at other institutions and come to believe that the problems they’re facing are essentially solvable.

Who leads the change effort?

Every change initiative needs a champion to drive it. “Somebody has to have a vision and passion to make change,” one reformer told me.

Change leaders for teaching evaluation reform come from a variety of different positions within an institution, including:

Faculty, including teaching faculty and department heads

Academic personnel committees or faculty governance bodies

Teaching center directors or staff

Dean’s or provost’s offices

Education research centers, such as UGA’s SEER

Interestingly, the change leader on many campuses is not housed in the same unit that “owns” the existing evaluation process. While buy-in at the policy level from process owners is commonly sought, evaluation “owners” and evaluation “reformers” are frequently two distinct groups. Who emerges as a champion for reform had less to do with institutional location and more to do with other factors, such as:

Subject matter expertise in the area of evidence-based pedagogy or the assessment of educational programs.

Experience crafting policy and navigating bureaucracy in higher ed contexts.

Capacity to serve as a project manager.

A tangible reason for the campus to trust them, either because the person is new in their position and had been given the leeway to define their first project (one reformer described this to me as the “honeymoon effect”), or because the person is an established and respected figure on campus already.

What motivates change?

Motivations for reform depend heavily on the role of the change leader. There is not one “right” way to articulate the pain points associated with existing evaluation systems, in part because the “existing system” at one institution is never identical to the “existing system” at another. Another way to frame this point is: modern approaches to teaching evaluation are seen as a corrective to a wide array of challenges facing higher education today.

“I basically do not look at my student evals at all.”

Here are some of the common threads I heard about what tends to motivate interest in modernizing teaching evaluation.

Faculty are motivated by:

Dissatisfaction with student evaluations of teaching, including widespread awareness of bias, disagreements with specific questions on the student survey instrument, discontent with how the surveys are used on campus (e.g., made public to students during registration for the next semester), and concern with grade inflation linked to a tacit agreement between students and instructors in which good grades are exchanged for good evals.

A desire to tell a more accurate and complete story of one’s teaching that can help others understand more fully what one does and appreciate its value. In particular, faculty are concerned that existing evaluation processes are insufficient to assess the breadth of work performed by teaching stream or adjunct faculty, who are often subjected to the same evaluation process as their research stream colleagues.

An interest in structure, transparency, accountability, and safeguards from personal politics. Faculty continue to be worried that opaque evaluation systems open them up to personal vendettas, petty grievances, subjective whims, and other factors that do not relate to their actual job performance and qualifications. As one change leader told me, “I got personally interested because I found my own path to promotion to be very convoluted.” Even though they did get promoted, they had “no clarity” and limited avenues for recourse if the decision had gone the other way. “All the ‘guidance’ I got was just oral histories passed down through the department,” they added.

An intrinsic desire to spend more time developing as a teacher, which can be difficult to prioritize when existing evaluation systems so heavily prioritize research. Modernizing teaching evaluations can support moving to a “three bucket” approach to evaluation, in which minimum levels of accomplishment are defined separately for research, teaching, and service (as opposed to all three being lumped together in one “bucket”). This desire for teaching to be recognized and rewarded in evaluation may be heightened in times when research funding is precarious. There was also broad consensus across my conversations that junior faculty are particularly keen on developing their teaching abilities and moving to evaluation systems that will help them grow.

Teaching centers are motivated by:

Discontent with teaching being undervalued in higher education, especially when compared to research. Teaching centers see evaluation reform as an opportunity to advocate for their institution’s teaching mission and as a rare avenue for putting teaching on a more equal footing with research—for example, in their relative weight in tenure and promotion decisions. In an interview with The Chronicle, Professor Amy Chasteen stated, “Let’s say you’re a university president and you want to invest in teaching because you believe that people can change or be affected in how they teach. Then where do you start? How do you motivate people when there’s no existing or pre-existing structures for reward, or any kind of a way to measure how good of a job they are doing?”

Concern that practice is not aligned with the research. While teaching centers may not be as personally harmed by existing evaluation practices when compared to faculty, they nevertheless see it as their responsibility to ensure that teaching is being evaluated in a methodologically sound and evidence-informed way. They recognize that you cannot reliably measure something if you haven’t defined what it is you’re measuring or articulated criteria by which to measure it.

The disconnect between evaluation and development. Student evaluations of teaching are severely limited when it comes to generating actionable formative feedback. One instructor told me candidly, “I basically do not look at my student evals at all.” Teaching centers worry that traditional evaluation systems don’t actually help faculty become better teachers, and in some cases, they may even cause harm. Negative experiences with unfair, unconstructive, or otherwise harmful comments—even if they are rare—can significantly impact instructors’ future willingness to engage with student evaluations of teaching. Teaching centers are interested in evaluation systems that motivate faculty to seek out developmental opportunities, which teaching centers are uniquely equipped to provide. Teaching centers are also invested in evaluation systems that can help them structure and communicate their developmental programming using a common language (e.g., through a teaching effectiveness framework).

The desire to create a more open and visible culture around teaching, where teaching is no longer viewed as something private that happens behind closed doors but is instead something that is discussed openly among colleagues.

Administrators are motivated by:

An interest in building more robust junior faculty mentoring programs, including ways to structure teaching development initiatives for new faculty.

The desire to get program or department-level indicators about the quality of an overall learning experience, or to have the ability to shift the unit of analysis from individual instructors to collective units or departments (e.g., experience in the “core curriculum” or other curricular units).

The possibility that more effective teaching strategies can improve student success, reduce DFW rates, and increase retention to support enrollment goals (which may be tied to funding formula).

An interest in streamlining compliance with accreditation processes or with institutional or statewide policies or collective bargaining agreements that require multiple sources of evidence to be used in teaching evaluations.

A commitment to ensuring that faculty are rewarded fairly and consistently both within and across academic units. This includes ensuring that faculty incentives align with institutional values. One change leader expressed this to me as, “We can’t improve the quality of teaching if we can’t signal the university’s value in that end product.”

A belief in capturing valid and reliable data that can be used to inform a wide range of institutional decisions.

For some institutions I spoke with, “bias” was a primary motivator for change among faculty. Other institutions worried about the repercussions of any change initiative that could be branded as “DEI-related” within the current political climate in the U.S. Change leaders should decide whether using “bias” will be helpful or unhelpful within their own context, and pivot to more methods-forward terms like “invalid and unreliable data” if needed.

What can stall progress at this stage?

1. Narrow focus on reforming the student survey instrument

It’s important from the beginning to make sure that stakeholders are focusing on the right problem. Because teaching evaluation has historically been synonymous with student course evaluations, some faculty do not immediately recognize any distinction between the two. “We’re trying to enable a mental model shift,” one change leader told me. “We want to go from ‘good teaching = 4.7’ to ‘good teaching is defined by our criteria.’” In particular, there is a common fixation on the particular questions, even the wording, on the survey. Moreover, institutions can feel locked into the longitudinal data generated by student surveys, creating a disincentive for change even when the data they’re capturing is poor quality.

“We want to go from ‘good teaching = 4.7’ to ‘good teaching is defined by our criteria.’”

In fact, faculty dissatisfaction with the survey instrument can be a useful starting point for reform, but the process can derail if the conversation stops at the instrument itself. Years can be spent in committees wordsmithing survey questions. Successful reformers are able to convert an initial interest in revising a specific instrument into a larger conversation about the overall evaluation process, emphasizing the need for more holistic approaches to evaluating teaching effectiveness beyond the student voice. In many cases, they also attempt to shift the conversation away from specific survey questions to how the survey is used within the overall evaluation process.

2. Reinventing the wheel

In the vast majority of cases, recognizing a problem with the status quo in teaching evaluation isn’t all that challenging. Almost all of the institutions I talked to reported that “everyone hates student surveys.” I frequently heard comments like:

“Nobody on this campus is happy with how their teaching is evaluated.”

“No one I know has confidence in the results of student evaluations.”

“We could always get people to agree on the problem. But mobilizing people to solve it was much harder.”

“Student evaluations are the thing everyone hates the most.”

Identifying the problem with student course evaluations is generally much easier than identifying the solution. Especially when institutions lack awareness about modern teaching evaluation systems, reform feels daunting, as if a solution had to be invented from square one. Trying to reinvent the wheel can quickly diminish an institution’s appetite for change.

One of the most powerful ways to overcome this barrier is to showcase models of institutions who have successfully made reforms already. Early teaching evaluation reformers are still working to refine their processes a decade later, but institutions who have used those early successes as a model have been able to make it to Stage 5 of this process in as little as one or two years. The more we are able to synthesize and act on lessons learned from past reformers, the more streamlined future reform efforts will become.

“We could always get people to agree on the problem. But mobilizing people to solve it was much harder.”

3. “This could never work at my institution”

Each institutional context poses unique challenges for reform. Sometimes teaching evaluations are already covered by a faculty union’s collective bargaining agreement. For some public institutions, statewide policy prescribes how evaluations must be conducted. Some larger universities are incredibly decentralized with no obvious place to institute changes. In my conversations, I saw significant changes happening at institutions of all types and sizes.

To avoid a stall, change leaders need to appreciate that modern evaluation methods can be operationalized in many different ways, including ways that may originate as developmental opportunities that do not require a vote by a faculty governance body, a large grant to fund the initiative, or an approval from the provost.

Many of the common obstacles you may be anticipating at these early stages already have proven workarounds, solutions, or mitigation potentials. I discuss many of these operational possibilities below, but the important thing for this stage is that change leaders believe they have agency to make meaningful changes in their context.

Stage 2: Select a Change Strategy

Key Steps

Craft an evidence-informed case for change that resonates strongly with your institutional context and immediately generates buy-in from campus stakeholders, including the faculty senate.

Determine whether your primary objective will be to create resources that empower individual departments to reform their own evaluation practices or to institute a new evaluation policy across an entire school or university.

How to communicate the need for change

In the last section, we reviewed various motivations different stakeholders may have for seeking changes to teaching evaluation. The next step is for the change leader to secure the necessary buy-in to proceed by taking the project to the provost, dean, faculty senate, or other appropriate body for approval. The goal at this stage is not to unveil a total solution, which may startle faculty and raise red flags, but rather to generate interest in the problem and establish an efficient channel for addressing it.

Here is a script outline that has helped generate buy-in with faculty at many institutions:

Decades of research has shown that student surveys do not accurately measure teaching effectiveness (see bibliography). We also know from experience that student surveys don’t allow faculty to tell their full teaching story in a way that allows others to understand and appreciate what they do.

We can’t have a fair, consistent, or transparent evaluation process if we’re all using different definitions of what counts as good teaching, and something as complex as teaching cannot possibly be measured by just one data source.

The feedback we get from course evaluations is not always constructive or useful. We get low-stakes developmental feedback from peers on our research all the time, yet we rarely get the same quality of feedback about our teaching.

So at a minimum, we need an evaluation system that provides clarity about what we mean by effective teaching, allows us to present a comprehensive picture of our teaching abilities using multiple sources of evidence, and gives us useful feedback about how we can develop as teachers.

A number of our peer institutions have already started to adopt systems like these, and it’s time that we start exploring how they might benefit us as well.

The words “clarity,” “consistency,” “structure,” “transparency,” and “equity” came back again and again when speaking with change leaders about how they communicated the need for reform. Traditional evaluation systems are widely perceived to be lacking these five critical qualities.

UGA has developed a tool to help assess readiness for teaching evaluation reform. This tool is specifically aligned to the “Departmental action teams” approach outlined below.

What are the different approaches to reform?

Teaching evaluation reform efforts are generally geared toward generating resources and/or changing policies. While these two strategies often overlap in practice, or shift from one to the other over time, we can conceptually place reform initiatives on a continuum from policy-forward to research-forward:

A policy-forward approach aims to enforce a set of consistent evaluation standards across an entire school, college, or university.

A resource-forward approach aims to make it easy for individual departments or academic units to adopt modern teaching evaluation methods of their own accord.

Generally speaking, policy-forward approaches require higher-level buy-in from campus stakeholders and, as such, take longer to implement. Resource-forward approaches, on the other hand, lower the barriers to adopting best practice and seek to incentivize and encourage change rather than to enforce it via policy. As such, policy-forward approaches tend to be more top-down, while resource-forward approaches tend to be more bottom-up.

“If you don’t know what to do, do this.”

In my interviews, seven basic configurations of reform emerged. I describe them below, ordered from most policy-oriented to most resource-oriented.

Institutional policy change. Requires all faculty be subject to a new teaching evaluation process. This approach always requires high-level buy-in from a faculty senate and provost’s office and is generally spearheaded by a faculty senate committee or delegated to the teaching center director. These policies may be stronger (e.g., specifying criteria for evaluation within given dimensions of effectiveness) or weaker (e.g., specifying that multiple sources of evidence be used). Examples include University of Baltimore, Bates College, UC San Diego, University of Oregon, Wake Forest, and the University of Georgia.

Sensible defaults. Establishes a comprehensive new teaching evaluation process, but does not require departments to use it. This approach may allow departments to opt-out, customize the default option to fit their needs, or provide multiple evaluation options to faculty. This was described to me as: “If you don’t know what to do, do this,” or “Even if departments change nothing, they still have a good process.” The idea is to nudge departments toward effective practice by making a good option very easy for anyone to use, even if it isn’t perfectly customized to a department’s specific context yet (customization can come later). Examples include University of Illinois and UCLA.

Leveraging existing policies. Several institutions I spoke with said that they started their reform effort assuming that the end goal would be to change university policy. However, once they dug into the policy, they found that it was much more aligned with modern approaches than what was actually being implemented in practice. Some policies may already require multiple sources of evidence for effectiveness be used; many policies do not specify that student course evaluations have to be used in faculty evaluation at all, or do not specify the weight they must carry in the overall evaluation process; and almost all policies allow multiple sources of evidence to be used, even where student evaluations are required. In these cases, reform took the shape of enabling departments to make existing policies work for them and align with modern evaluation approaches. Examples include UC Irvine, Northwestern University, and University of Colorado Boulder.

Departmental action teams. Build an internal consultancy to work with departments to reform their own policies and practices for evaluation. While departments generally have a high degree of autonomy to determine how faculty are evaluated, they rarely have the bandwidth to implement change on their own. External facilitators—such as centers for teaching and learning or education research centers—work with department representatives (sometimes department chairs, sometimes interested department members) to make reforms. This usually involves a small grant to program participants. Examples include University of Georgia, UCLA, University of Colorado Boulder, University of Kansas, and UMass Amherst.

Faculty learning communities. Similar to departmental action teams but organized in a cross-disciplinary manner. Unlike department-based groups, however, these communities may be less concerned with changing departmental policies and more concerned with helping individual faculty across departments assemble a teaching portfolio using a framework that may not have been adopted at an institutional level. This works well when teaching portfolios are accepted within but not required by current evaluation policies (see leveraging existing policies above), such that individual faculty can use the portfolio they produce in the learning community for their own evaluation process without necessarily seeking a policy change. Tapping into existing institutional structures for setting up FLCs can be an effective way to get a bottom-up effort off the ground. The primary example of this approach is Boise State.

Instrument alignment. When institutions are not able to change the criteria by which teaching is evaluated, they may opt to improve the quality of existing inputs into the evaluation process. This usually means aligning evaluation instruments (such as the teaching statement, peer observation protocols, and student course evaluation surveys) with a teaching quality framework, even if that framework is not ultimately used by reviewers. The primary example of this approach is Penn State.

Developmental only. Because modern approaches to teaching evaluation provide formative feedback to guide instructional development, it is possible to add developmental programming aligned with modern approaches without actually changing the evaluation process at all. Such programs generally center on a teaching quality framework, allowing faculty to develop a common language about what effective teaching looks like. Faculty can then self-assess areas in which they would like to develop, and centers for teaching and learning can create targeted programs to guide faculty progress. The primary example of this approach is Appalachian State, who runs a Teaching Quality Framework grant program.

How to mitigate resistance to change

Clearly, there are many different ways to seek change when it comes to teaching evaluations. Regardless of the specific shape a reform effort takes, however, one thing we know about higher education is that change is hard. Competing change initiatives, shifting personnel in leadership positions, overworked faculty with little time for service, complex committee structures, and limited resources are all factors that can impact progress but generally fall beyond our control. Large scale policy changes, in particular, can take years if not decades to accomplish.

Several institutions reminded me that there is no resistance-free road to change in higher education. Some amount of pushback should always be expected. However, throughout my conversations, three different patterns seem to cut across institutions as ways to mitigate external risk factors and increase the probability of success. These patterns will not eliminate the natural frictions of change, but they can significantly temper the sources of extreme opposition that can grind progress to a halt.

1. Be opportunistic in advocating for comprehensive change

The majority of institutions I spoke with did not start out seeking to transform how teaching was evaluated across the entire institution. Very often, reform started when faculty took an interest in one very small piece of the larger evaluation puzzle. This could include philosophical issues like bias in student course evaluations or in some cases be purely logistical, such as the software being used for course evaluations was built on an outdated programming language and needed to be replaced. In several cases, departments were interested in formalizing peer observation protocols, and many teaching centers are already offering services in this area. Other opportunities for getting teaching evaluation on the agenda could include tapping into existing strategic planning, internal review, or accreditation cycles.

There is not one “best” place for the conversation about change to start. What matters is change leaders’ ability to take advantage of the conversations and issues that crop up organically on their campus. Meeting faculty where they are is key. What may start as a straightforward procurement process for a new student survey vendor might end up leading to larger-scale questions about how teaching is evaluated; what starts as an email about the teaching observation protocol might spiral into a semester-long faculty learning community on modern evaluation systems.

Once faculty’s interest in an issue is piqued, they generally want to solve it the right way rather than tinker at the margins. Successful change leaders are able to seize opportunities as they arise, before interest fades and faculty turn their attention to other pressing matters. Showing faculty how their concerns connect with the wider movement to transform teaching evaluation can be a powerful way to shift their thinking away from ineffective and superficial half-measures and toward more meaningful and lasting change that gets at the root of the problems with traditional approaches.

2. Shift culture before shifting policy

There is no consensus on whether requiring all faculty evaluations to conform to modern standards should be the end goal of reform. Even institutions who started with the ambition to require a new approach often ended up dialing that back, allowing for opt-outs, or repeatedly deferring the deadline by which all evaluations must be brought into compliance.

Many institutions found that the costs involved in mandating comprehensive new approaches outweighed their benefits. Even under the best of circumstances, top-down requirements are viewed suspiciously and tend to generate a vocal minority of faculty in extreme opposition who can threaten to derail the entire change initiative. Changing the rules before faculty can experiment with new methods and evaluate them first-hand is a recipe for failure. In general, institutions I spoke with believed that changing culture was a more important first step than changing policy. As the saying goes, “Culture eats strategy for breakfast.”

The TEval approach describes change strategies as bottom-up (driven by a faculty member), middle-out (driven at the department level), or top-down (driven by a college or institution). Most institutions I spoke with seemed to have success starting with a cultural shift within departments who sought out change and then, over time, proceeding to a policy level. This passage from Transforming College Teaching Evaluation is instructive and rings true of the conversations I had:

“Changes in one department are likely to raise interest or questions in other departments since deans or college-wide review committees typically expect faculty promotion and review materials to be organized in parallel fashion across departments…thus, change in one unit may have a ripple effect across the institution.”

When a department approaches a dean with an interest in changing how teaching is evaluated within their department, the dean may choose to treat their efforts as a pilot whose processes, if successful, could be rolled out to other parts of the institution.

Starting with a bottom-up, faculty-driven approach builds a critical mass of natural allies and ambassadors across campus, generating goodwill in place of suspicion when it comes time to enact policy changes. Far and away, faculty are most likely to trust their fellow faculty members when it comes to believing that the changes being proposed will work for them and not against them. Collaborating with interested faculty members in a grassroots, bottom-up way to hear their motivations for change, seek their input on proposed changes, and earn their trust going forward is an invaluable starting place for any initiative. Of course, keeping administrators abreast of your developments from the outset is important too, but keeping deans in the loop—or seeking their permission to start working with departments—should be distinguished from a top-down approach in which administrators seek to impose policy reforms without laying the proper groundwork with rank and file faculty.

“We erred on the side of overcommunicating. Our goal was for faculty to get sick of us.”

Even some institutions who aimed for institutional policy change from the outset worked exhaustively to generate buy-in from faculty. This can take the form of listening sessions, focus groups, and periodic updates to faculty governance. These sessions did not ask faculty to do the work of creating an entirely new evaluation process, but rather gathered their input to inform decisions made by those who would eventually design the new system. One change leader who took this approach told me, “We erred on the side of overcommunicating. Our goal was for faculty to get sick of us.”

3. Use a weak policy to start shifting culture

Another reform pattern that showed particular promise was using a minor policy change to catalyze a major culture shift. The best example of this is the University of Georgia. Even within a large university setting where consensus on new policies is notoriously hard to achieve, UGA passed a teaching evaluation policy that said simply that peer observation must be available to faculty who want it.

The brilliance of this policy was that it was about adding another option as opposed to requiring a wholesale shift in process. The narrowness of the policy proposal effectively minimized opposing faculty voices, wasting less time arguing in committees and leaving more time to institute real change. Culturally, this minor policy change was sufficient to start a much larger conversation about teaching evaluation reform across departments. And because departments would now have to set up a new peer observation protocol, many of them built on this momentum and took the opportunity to engage in a more holistic reform effort. By providing external resources to guide and support departmental reform, UGA incentivized and encouraged departments to make larger changes when only small ones were actually required.

Minimal policy proposals that can nevertheless prompt broader reforms include:

Requiring or allowing at least two sources of evidence be used to evaluate teaching effectiveness.

Requiring or allowing instructors to reflect on their student evaluations of teaching and set goals for future development.

Requiring or allowing the use of peer observation.

Requiring or allowing faculty to submit a reflective teaching statement.

Allowing individual faculty to choose between the traditional evaluation process created by their department or a reformed process created by the institution.

Requiring that only new faculty use a reformed evaluation process, but allowing existing faculty to opt-in if they choose.

In these cases, the primary purpose of the policy is not to impose a universal solution to teaching evaluations, which most faculty will resist, but to give faculty a reason to start working on a problem they actually care about.

As noted above, you may actually find some of these minimal policies already exist in your institutional policy documents, even if they are not currently being implemented. As such, you may not even need a minor policy change, but rather to start enforcing an existing policy. UC Irvine took this approach after discovering that university policy already required multiple sources of evidence, even though only student course evaluations were actually being used. They leveraged this discovery to create a robust institutional culture of writing reflective teaching statements, and their newly established center for teaching and learning quickly garnered credibility for helping faculty learn to craft these important documents.

What can stall progress at this stage?

1. Top-down policy proposals generate extreme opposition

Securing buy-in from campus stakeholders is the most politically fraught stage of the implementation process. It’s important to keep in mind that being evaluated is an inherently touchy subject in any profession—people don’t like to be judged. One interviewee described teaching evaluations to me as a “third rail”: even though everyone knows it’s broken, no one wants to touch it. Moreover, when evaluation impacts important decisions like tenure and promotion that affect people’s careers and livelihoods, the stakes are even higher. For many, there is a sense of safety that comes from the familiar—course evaluations are “the devil you know”—and one of the leaders I interviewed mentioned how faculty have adapted to traditional approaches, for example, by bringing candy to class in hopes of garnering higher ratings on student surveys. “People are afraid we want to get rid of the thing they’re already good at,” they noted.

One of the most surefire ways to relieve the natural anxiety around evaluation is to communicate from the beginning that any new policies will be opt-in for existing faculty, or to take an opt-in approach until a groundswell of faculty can make the case for policy change that doesn’t feel like it is being imposed on them from the top down. One institution told me that making the process opt-in was so effective at erasing individual opposition that they actually worried that they were missing out on opportunities to address legitimate faculty questions. “You don’t want people ‘killing’ the program, but you do want to hear their concerns. By now we actually have the answers to most of the common concerns, but if we don’t hear them, we can’t respond to them,” one leader told me.

2. “If we build it, they will come”

Even in cases where changes are required by policy, individual departments do not have the capacity to make changes on their own. As one change leader told me, “You can’t give department heads resources and ask them to implement them. Even if something is easily deliverable, you have to have someone leading the charge.”

“We can’t increase the intensity of evaluation without also increasing the intensity of support.”

One potential pitfall of a resource-forward approach in particular is to generate a lot of documents and guides about how to adopt a modern teaching evaluation process that, in practice, are never actually used. The mindset of “if we build it, they will come,” does not have a good track record of success when it comes to teaching evaluation. “We can’t increase the intensity of evaluation without also increasing the intensity of support,” as one change leader put it.

While the “building” phase is certainly necessary, successful reform efforts locate a project manager function outside of the department to drive adoption. The project manager (usually an existing teaching center staff member or faculty fellow, post-doc, or fellow in the provost’s office) takes responsibility for the overall change initiative, recruiting departments to make changes and keeping them accountable over time. The project manager may gain legitimacy and authority from helping to implement new campus policies, offering financial incentives to participating faculty, building relationships with department chairs, being given an official mandate by the faculty senate, or other mechanisms.

“…you have to have someone [outside the department] leading the charge.”

3. Death by committee

With a few notable exceptions, change initiatives were more successful and more efficient when led by a member of staff (such as a teaching center director), administrator (such as a Vice Provost for Academic Personnel), or faculty fellow with course releases than by a faculty committee. In several cases, a faculty senate delegated the change initiative to a teaching center director as opposed to trying to solve it in committee. Allowing someone with expertise in teaching effectiveness to guide the process streamlined the effort by allowing faculty to defer to the research on teaching and learning rather than trying to hash things out based on what they personally believe good teaching looks like. As one reformer put it, “Faculty respond to competence.” Another told me, “Faculty actually appreciate the hand-holding.” It keeps them in the loop while taking work off their plate.

Stage 3: Adapt a Teaching Effectiveness Framework

Key Steps

Review existing frameworks and adapt the language of the one you think works best in your institutional context as necessary.

Emphasize to faculty the broad applicability and evidence base of the selected framework while allowing departments some degree of customization. When appropriate, seek faculty approval on the framework template.

Establish criteria for proficiency for each dimension of the selected framework.

Align faculty development opportunities (workshops, institutes, grant programs, badging programs, etc.) with the selected framework.

Will faculty accept a framework?

In some cases, change leaders felt that proposing a teaching effectiveness framework would be politically risky and derail the reform effort. For this reason, a handful of institutions chose to skip this stage and concentrate their efforts on expanding the type of evidence allowed or required in evaluation files. Some institutions regretted this choice. One change leader who skipped this step told me, “I feel like we did everything backwards.”

“Criteria help me do my job better.”

The problem with skipping this stage is that any ensuing reforms will inevitably be plagued by the same problems that made student course evaluations poor indicators of teaching quality to begin with. Any assessment expert will tell you that without clearly defining the construct you intend to measure, you will never end up with a valid and reliable measurement process. Trading students’ subjective understandings of good teaching for faculty’s subjective understandings of good teaching does not provide the construct validity required for meaningful assessment. Moreover, without defining the components of effective teaching, centers for teaching and learning and other faculty development initiatives will not be able to align developmental programming with the new evaluation system. A teaching center director told me, “Criteria help me do my job better.”

Faculty resistance around teaching effectiveness framework generally falls along two interrelated concerns:

1. The fear that a framework will be overly prescriptive

Faculty do not want to feel like a framework is putting them in a box and dictating how they should teach. They may envision a framework as a checklist of things they need to do in the classroom (which a well-defined framework is not). To assuage this fear, several institutions avoided introducing faculty to proficiency criteria when first presenting the framework, as this would have fed into the perception that the framework is prescriptive. They also pitched the framework as being sufficiently broad to capture a wide range of teaching practices. The purpose of a framework is to define various high-level, cross-cutting dimensions of good teaching without dictating how those dimensions play out in particular teaching contexts.

“I want to help give faculty language to validate their experiences in the classroom.”

Barbeau and Happel (2023) provide language that may be helpful in this effort:

“Research provides invaluable guidance on effective teaching practices; however, successful implementation of those practices depends on a broad range of variables, including but not limited to instructor persona, students, discipline, class size, modality, and course and institutional context… We needed an instrument that was both flexible enough to accommodate individual expressions of good teaching and comprehensive enough to provide a unifying language and common understanding of the components of good teaching.”

Another strategy that builds on this is to pitch the framework as a common language for talking about effective teaching, rather than as a “definition.” As Lindsay Masland explained on a podcast with Derek Bruff:

“[A] teaching quality statement…essentially defines the major areas that we want to talk about when we talk about quality teaching, which I think is an important but subtle point. Our framework doesn’t say this is quality teaching and this isn’t.”

A change leader I interviewed echoed this approach, saying “I want to help give faculty language to validate their experiences in the classroom.” Another stated, “Our definition [of effective teaching] helps people get credit for things they’re already doing that they didn’t even know to include.”

2. The fear that a framework cannot possibly capture effective teaching across disciplines and contexts

Faculty do not want to feel that a new evaluation system is imposing a “standardized” or “one-size-fits-all” approach. As one change leader told me bluntly, “People will lose their shit if you say ‘standardization.’” (Tip: use “consistent” instead of “standardized.”)

Faculty are unlikely to be familiar with the current state of scholarship in educational development, which continues to find that, across diverse contexts and modalities, good teaching has a core set of many common qualities—that good teaching is good teaching. If you buy a college teaching book today on teaching with accessibility in mind, or on teaching online STEM classes, or on alternative grading practices, you might be surprised at how similar the strategies are that they recommend. Yes, these strategies may be implemented differently across context and modality (e.g., a small humanities seminar, a large STEM lecture, a lab section, etc.), but the underlying pedagogical principles are generally the same.

“Everyone wants to customize the rubric at the start, but by the end, everyone basically uses the same form.”

It turns out that the thing most faculty imagine when you say “definition of good teaching” is not congruent with what actual teaching quality frameworks look like. Faculty tend to find looking at an actual proposed framework much less scary than imagining a “definition” of good teaching in the abstract. As such, institutions have found that the best way to ameliorate this potential concern is simply to present faculty with a framework. Providing some footnotes to show how the framework is grounded in evidence-informed research and not just subjective perceptions can help quickly generate buy-in (see bibliography).

Even in workshops where faculty are invited to customize the framework to fit their department, several institutions reported faculty starting from the assumption that they would need to change everything and then ending up making only minor adjustments. One change leader told me, “In the beginning, faculty resist a one-size-fits-all approach and assume it can’t be done and won’t work. Everyone wants to customize the rubric at the start, but by the end, everyone basically uses the same form.” After seeing a draft framework, faculty usually still want to tweak the language a bit, but overall they are more comfortable with the idea of using a framework.

Be clear that you are not trying to police which teaching techniques are “in” and which are “out,” but rather that the framework provides a common language for talking about the various facets of an effective teaching practice, which can take on very different forms depending on the specific teaching context. Think of the framework as a way of structuring a conversation around teaching, not dictating what teaching must look like across the board. In fact, frameworks tend to recognize and reward faculty who bring their authentic personality, unique strengths, and discipline-specific experiences to the table, as these all contribute to cultivating a high quality learning experience.

How to choose the right framework

The most influential teaching quality framework is the University of Kansas’s Benchmarks for Teaching Effectiveness. First created in 2017 by KU’s Center for Teaching Excellence, this became the foundation for the TEval approach. Because it was one of the first frameworks, almost every institution I spoke with said that they either adapted or reviewed this framework when creating their own. As a result of this shared lineage, most of the frameworks being used by institutions today have a high degree of overlap.

In all of my interviews, I did not encounter a single framework that I felt was of poor quality or radically contradictory to other frameworks. Given the developed state of available frameworks, adapting an existing framework is strongly preferred over starting from scratch. Here are a few considerations to keep in mind while choosing a framework to adapt:

How developed is the framework? More established frameworks will not only provide a description of each dimension, but will also provide things like proficiency criteria for each dimension and a list of evidence to document each dimension. One advantage of using the TEval framework is that there’s a whole book of supporting materials and guidance on how to implement it (Transforming College Teaching Evaluation) along with materials available on the TEval website.

How many dimensions does it have? Part of the art of designing a framework is proposing as few categories as possible but as many as necessary. In general, the number tends to range between four and seven. Some frameworks, like the framework at App State, have sub-dimensions within each larger dimension. UCLA’s framework has only four dimensions but enumerates a number of different “common practices” under each, similar to the Critical Teaching Behaviors framework. In general, the more dimensions you have, the more paperwork is required and the more time it takes to complete the evaluation (though there are ways to mitigate this).

How does it incorporate equitable and accessible teaching? Some frameworks pull out inclusive, equitable, or accessible teaching as a separate dimension. The current political situation at some institutions may block this approach. Other frameworks incorporate inclusive teaching techniques as a cross-cutting concern that gets embedded within each dimension, making it much easier to adapt language to different political contexts.

How does it rate proficiency? The criteria for proficiency associated with a framework may actually be more variable between institutions than the frameworks themselves. Some frameworks choose to use quantitative rubrics, others stick with qualitative labels such as “developing,” “proficient,” and “accomplished.” Rubrics have as few as two rating scores and as many as five. Most of the reformers I interviewed agreed that using qualitative labels is preferred to quantitative scores, which tend to revert back to judging teaching by a single average—something faculty already disliked about using student evaluation scores.

How well does it hold up across teaching modalities and contexts? The best frameworks are agnostic to class size, teaching modality, discipline, and other variables. For example, a mostly online institution may want a framework that avoids frequent language about “classrooms.” Make sure to consider the breadth of teaching activities across your institution before committing to a framework.

What can stall progress at this stage?

1. Wordsmithing

Try as much as possible to avoid soliciting widespread faculty input on the specific wording of the framework. These conversations can take a lot of time to yield minimal or even negative impacts on the overall effort. Let the teaching center director or staff adapt a framework that reflects your institutional context, then present it to a small faculty senate subcommittee or other trusted group if necessary. Spend your time with the full faculty explaining how you developed the framework, how it is grounded in research, and any questions they have about it. Be prepared to defend the decisions you made rather than instantly giving into requests to change the wording.

2. Too much customization

In spite of faculty’s resistance to “one-size-fits-all” approaches, it is critical to remember that customization always comes with a cost. The usefulness of a shared definition of effective teaching deteriorates when departments are given too much latitude to customize it. The more a framework is customized, the less able institutions will be to leverage it for faculty development programming, make cross-unit comparisons, utilize portfolio technologies that can reduce logistical busywork, ensure accessibility, keep accurate records of evaluation processes over time, update and revise dimensions and processes, and link evaluation processes to other institutional goals and initiatives such as accreditation and strategic planning.

“Not everything has to be bespoke.”

A common theme that runs through these pitfalls of customization is that the change leader becomes unable to maintain, revise, evaluate, or improve processes once they are handed over to individual departments, who generally lack the capacity for regularly performing these functions. Revising one common framework, for example, is significantly more manageable and takes much fewer people hours than attempting to help 50 different departments refresh their own fully customized framework.

The associated costs of customization are almost always overlooked when first configuring a new process. The role of the external facilitator serving in the project management function in this case is to protect the integrity of the institutional framework as much as possible by explaining why it is the way it is. As one interviewee put in, “Not everything has to be bespoke.” Rather than opting for a “bespoke” solution that will be out of date in six months without anyone in the department willing to revise it, it works better to guide faculty toward a “sensible” solution that might not be perfect but that will be more sustainable over the long term (see “sensible defaults” above).

Departments should focus their energies on elaborating the framework as opposed to changing its basic features. A good way to do this is to allow departments to specify “What this looks like in our department” for each dimension. Rather than customizing the dimensions themselves, departments can give specific examples of how a given dimension plays out in their disciplinary setting and institutional setting. You can also allow departments to provide example documents to faculty to showcase how to apply general guidelines in their submitted materials. Finally, you can clarify that not all evaluations need to include every dimension if they are not applicable (for example, if a faculty member does not have mentorship responsibilities, that dimension can be left out of their evaluation).

Two domains which some institutions did find it necessary to include some level of customization were online programs and clinical education programs. Many of these customizations, however, can be made by simply removing certain dimensions from the evaluation, as discussed above. For example, an online instructor’s rubric may center more on course design than on course facilitation. An adjunct evaluation in which the instructor was not authorized to modify the course design may do the reverse and weight course facilitation heavily while omitting course design. In general, there was an interest among administrators and teaching centers to find modality-agnostic forms of evaluation that built in options for minimal customizations where necessary.

Stage 4: Expand the Types of Evidence

Key Steps

Align existing evaluation instruments (student surveys, peer observation protocols, etc.) to a teaching quality framework.

Modify student surveys to indicate that they are surveys of the student learning experience, not evaluations of teaching quality. While student surveys may be (and often are) used within the teaching evaluation process, they should not be treated as evaluations in themselves.

Provide structured guidance, processes, trainings, templates, and models for two key pieces of evidence: conducting peer observations and writing reflective teaching statements.

Introduce faculty to the three “voices” or “lenses” of evaluation and develop a matrix indicating which sources of evidence can be used to demonstrate effectiveness across teaching dimensions (see example below).

Put checks in place to ensure that portfolios of evidence cannot ultimately be boiled down to one number purporting to represent overall teaching effectiveness and that the student voice is not given disproportionate weight.

Where to start

Sometimes matrices of evidence can make things look more complicated than they actually are. In practice, there are three key forms of evidence—one from each lens—where institutions put almost all of their effort. They are:

1. The student survey

Most institutions seeking comprehensive reform will, at some point, briefly discuss abolishing the student survey altogether. I have not yet heard of a case where this has actually happened, and even the most ardent critics generally see some potential usefulness in the survey, if only for the optics of soliciting student input.

There are many things that can be done to reform the survey instrument, and I do not review the literature on modern student survey design here. UGA’s DeLTA project has perhaps the best and most succinct resource specifically on aligning evidence from the student voice with modern approaches to teaching evaluation, but there are many other resources available as well. In my interviews, reforms to student surveys often centered around the following:

Replacing “evaluation” language with “reflection” or “experience” language. For example, “student evaluation of teaching” became “student course reflection survey” or “student experience of learning survey.” This also involves rewriting the questions to be aligned with an experience survey as opposed to an evaluation.

Mapping specific questions to particular dimensions of a teaching quality framework. In most cases, this also meant removing totalizing questions such as “What was the overall quality of this course?” and instead focusing on specific dimensions of teaching quality to improve construct validity.

Providing a bank of validated questions as opposed to letting units or institutions write their own.

Modifying how the survey is used within the overall evaluation process. Some institutions allowed reviewers to see only qualitative feedback and not the quantitative averages. Some used student surveys primarily to identify low-performing outliers, disregarding or de-emphasizing numerical differences above a certain minimal threshold. Some institutions provided reviewers only with a summary of the evaluation written by a third-party. At least one institution I spoke with stated that their faculty union’s collective bargaining agreement stipulated that student evaluations could not be required for annual review or tenure files, though they could be added optionally at the faculty member’s discretion.

Offering guides and trainings about the types of bias that research has found with student surveys and general best practices for using assessment surveys from a statistical point of view, enabling reviewers to better interpret the data in front of them.

2. The reflective teaching statement

Since every institution I spoke with already had an established student survey, many reform initiatives simply left that in place as-is and start building out a second “lens”—either the peer lens or the self lens. The benefits of working on the self lens first are twofold.

First, the self lens is generally easier to implement than the peer lens. Most existing evaluation systems already require or allow for some sort of teaching statement or narrative, so rather than adding a new piece of evidence entirely, you just provide structure and guidance for how to craft the teaching statement around a teaching quality framework.

Many faculty report that it’s actually easier to write a teaching statement if they have a better sense of the criteria they’re being evaluated on. Without a framework, many faculty tend to take a “kitchen sink” approach to teaching statements, where they throw in lots of unstructured information in hopes that something or other will resonate with the review committee. This also makes things tricky for reviewers because teaching statements vary so vastly from one to another that it is hard to apply a consistent standard across the board. A framework removes guesswork on both the writing and reviewing ends, providing a reliable structure to follow in highlighting their teaching achievements.

Second, reflective teaching statements are often used to mitigate against the potential harms of student course evaluations. Several institutions I spoke with aimed to de-emphasize student surveys by allowing instructors to reflect on their survey results, contextualize them, and reflect on how they plan to develop in their courses in the future based on student feedback. Rather than focusing on the raw survey scores, evaluation committees were being guided to assess the reflectiveness by which faculty were interpreting and responding to those results. See for example, the Reflective Teaching Statement guide from UCI and the Self-Reflection Quick Start Guide from Penn State.

3. Peer observation

Institutions using the departmental action teams model to make change—such as UGA and CU Boulder—often focused their energies on building out peer observation protocols at the department level. Tackling the peer lens first may also work well for institutions whose teaching centers have already been investing in building out peer observation protocols.

In general, once you have a framework in place, developing a peer observation instrument becomes a much simpler task, as institutions simply structure the observation around behaviors associated with each dimension of teaching effectiveness. Here are two examples from KU for peer review of online classes and peer review of on-site classes (docx download).

Several institutions stressed the need not only for peer observation instruments but also training for observers. Many peer observations tend to descend into subjective reflections in which the observer expresses how they would have taught the class. Or they may focus their review on pet peeves or other aspects of the teaching performance that don’t ultimately impact the learning experience for students. Untrained observers using open-ended instruments have the risk of being just as unhelpful and biased as student surveys. On the other end of the spectrum, some peer reviews tend to resemble “love letters” that make grandiose claims sparsely supported by evidence. One change leader noted that while faculty are often socialized by their discipline into giving each other feedback on research, they lack models and practice when it comes to having constructive, collaborative conversations about teaching.

Other evidence

The three pieces described above—student surveys, the reflective teaching statement, and the peer observation—are the primary sources of evidence created specifically for the teaching evaluation process. The vast majority of remaining evidence that instructors may submit as part of their portfolio of evidence comes from assembling existing artifacts from their teaching and do not need to be (and actually should not be) created for the purposes of evaluation. These include things like student assignments, syllabi, other course materials, examples of student work, grading rubrics, a list of publications on their teaching practice, certificates from their center for teaching and learning, etc.

How to minimize reviewing time

One of the most common and serious stumbling blocks to teaching evaluation reform is that more evidence means more time required to both prepare and review evaluation files. In general, the increased demands placed on reviewers tend to be more of a sticking point than the time required to prepare the portfolio.

This poses a serious risk to the entire teaching evaluation reform effort because if unreasonable demands are made on reviewers’ time, this will impact both the accuracy of their evaluation as well as its ability to provide useful formative feedback to the instructor under review. There are several effective strategies institutions have mobilized to make reviewing time much more manageable:

Use fewer dimensions. As noted above when discussing frameworks, the more dimensions you have in your teaching quality framework, the more likely you are to have documents and notes on each one. Evaluation files can quickly become unwieldy when frameworks attempt to be too fine-grained in their elaboration of good teaching. TEval’s seven dimensions seem to be the upper end.

Use an efficient workflow. More documentation often stresses existing evaluation workflows. You don’t want reviewers spending all their time trying to find which file is in which folder, requesting permissions to view, going back to the rubric and having to reload the page, and so on. Efficient workflows allow reviewers to concentrate only on high-level tasks. One institution I spoke with used a PDF form in which instructors would manually type out the filenames of the documents they wanted to include as evidence, which reviewers would then manually have to hunt down somewhere online. Reformers spend the majority of their time making sure the instruments, frameworks, rubrics, and other evaluation materials are of high quality, but frequently overlook the nitty-gritty details about which technologies and workflows will be used to actually implement the new evaluation system, which can make or break the entire reform effort. Using an external project manager can help optimize the workflow while keeping things moving for reviewers.

Lean on narratives over documents. A simple yet transformative innovation pioneered by UCLA is to center the entire evaluation file around a narrative as opposed to around files in a portfolio. In this approach, instructors describe their teaching practices that align with a given dimension of teaching effectiveness and provide documentation only occasionally. This model does not expect evidence to stand on its own, so even when evidence is included, the instructor has already given reviewers an indication of what to look for. This allows the portfolio to contain fewer documents overall while also making the documents that are included easier to review quickly. In most cases, reviewers need only check the documents briefly to verify what was already written in the narrative, almost like a footnote. When implemented well, this strategy can vastly reduce the amount of reviewing time required without negatively impacting the overall quality of the teaching portfolio. UCLA has even found that empowering faculty to craft their own teaching narrative encourages more analysis and reflection—qualities they aim to develop through the holistic evaluation process.

What can stall progress at this stage?

1. Prematurely incorporating instruments into evaluation processes

Whenever you propose a new instrument or revise an existing one, faculty are immediately going to have questions about how the changes will impact the evaluation process for annual review and tenure and promotion. In fact, there is likely to be more widespread faculty interest and concern about the evaluation process than the evaluation tools. Change leaders put themselves in a difficult position when they try to develop new instruments while having to explain how they will be used for evaluation at the same time (and before their usefulness has actually been demonstrated).

Keeping with the theme of changing culture before policy referenced above, it is important that critical pockets of faculty buy into using the tool before trying to integrate it fully into the evaluation system. For example, enacting a policy requiring peer observation is usually not a good time to start building a peer observation protocol. Instead, a peer observation protocol that has been serving certain parts of the institution effectively for several years could become the basis for an institution-wide policy. Faculty will be more comfortable incorporating instruments into policy solutions once they have evidence that a tool has already been piloted with success on their campus and can hear their colleagues attest to its value not only in theory but also in practice.

2. Drowning in evidence

“Portfolio” can be a scary word—it just sounds like it’s going to take a long time to compile and to read. One institution I spoke with stipulates that teaching packets should not exceed 100 pages. This is very long and is almost sure to induce resistance among faculty. Even if faculty are aligned in their values for pluralizing the sources of evidence used in teaching evaluations beyond student surveys, they may get spooked if they feel that they’re now going to submit (or review) hundreds of pages of documentation. Moreover, systems that invite faculty to throw “everything but the kitchen sink” into their portfolio risk overwhelming reviewers with documents that make it difficult to see where actual gaps exist.

Peer observation, in particular, can easily become a touchy subject among faculty unless significant groundwork has helped foster a culture of openness around teaching that builds trust and respects academic freedom. It’s important to keep in mind that modern approaches to teaching evaluation do not insist on any one piece of evidence—in fact, they are designed specifically to avoid this kind of dependency. Embracing modern teaching evaluation means giving faculty choices about how best to present their teaching story and not requiring them to learn how to prepare multiple new types of evidence at once. The TEval framework, for example, only requires that evidence from two lenses rather than all three be presented for each dimension of effective teaching.

3. Concerns about cherry picking

Some institutions worried that giving faculty too much choice in selecting their evidence would lead to cherry picking. Do the documents that instructors choose to include in their portfolio accurately represent their total teaching practice, or are they themselves a biased sample? Should there be required pieces of the portfolio to mitigate against this? Certainly, creating one detailed grading rubric for the purposes of evaluation is very different from consistently using structured rubrics throughout one’s teaching.

One practice to address this concern is to ask faculty to describe in their narrative for each dimension how their artifact relates to their total teaching practice. Another is to train reviewers to triangulate the available data to see where it tells a consistent story and where gaps might exist. In this case, the question becomes less about whether one specific document is indicative of the instructor’s total teaching practice and more about whether the portfolio as a whole demonstrates effective teaching. This is one reason why TEval requires two forms of evidence for each dimension. A third mitigation strategy is to require evidence with multiple timestamps; for example, encouraging classroom observations to take place on multiple days, not just a one-and-done approach.

In general, most institutions believed that giving faculty agency to tell their own teaching story outweighed concerns about potential cherry-picking.

Stage 5: Evaluate Changes and Share Learnings

Key Steps

Define success criteria that cover not only whether the process is being implemented as designed but also whether the design is effective and leading to real impact.

Ensure that new processes being implemented at the department level are still visible to change leaders so that assessment and continuous improvement can occur. Ensure there are proper data collection processes in place so that post-implementation evaluation of new systems can occur.

Regularly review impact data and continue optimizing the evaluation process even beyond an initial pilot phase.

When appropriate, publish, present at conferences, post online resources, or otherwise share lessons learned—both successes and failures—in the growing community of teaching evaluation reformers.

How to define success